Requirements engineering is a foundational step in developing successful software projects. It involves understanding and documenting what a client needs from a software product, which is crucial for the project’s success. This guide aims to help software engineering students navigate the requirements engineering process, covering elicitation, elaboration, validation, and the creation of detailed specifications.

Requirements define the expectations for a software system. They can be categorised into:

Requirements elicitation is the process of gathering requirements from stakeholders. It’s essential for understanding the project’s scope and ensuring the final product meets the client’s needs. Elicitation involves communication with the client to uncover the core needs and expectations for the project.

Before meeting with the client, conduct background research on the project domain and potential competitors. This preparation helps formulate relevant questions and understand the client’s industry.

After gathering initial requirements, the next step is to refine and validate them.

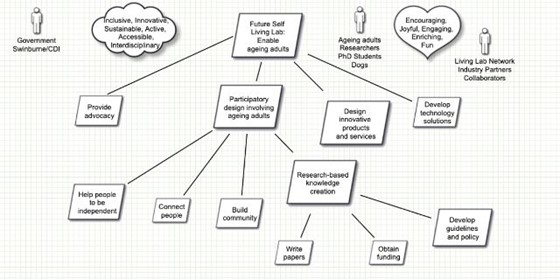

Use motivational modelling to visually represent the system’s goals and stakeholders’ needs. This approach helps clarify the project’s objectives and ensure alignment with user expectations.

This technique allows the functional, non-functional, and emotional goals of the system to represented in a diagram. The benefit is that diagrams are often easier to read compared to written requirements, and emotional requirements are also considered. Motivational modelling is done through brainstorming a list of the key requirements of the system and stakeholders involved. The list is called a DO/BE/FEEL/WHO list, and should detail:

This list is then converted into a hierarchical diagram, as shown below. This is a great starting point for teams to confirm the understanding of the project requirements, with the bottom leaves corresponding to user stories.

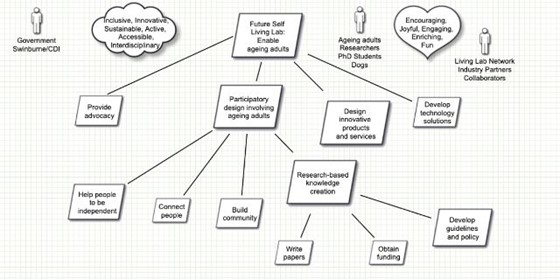

Personas are carefully crafted profiles that symbolise the key characteristics of various user groups of a product. These archetypical users help development and design teams gain insights into the product’s user base, fostering empathy and understanding. By embodying the goals, needs, behaviours, and pain points of real users, personas guide the decision-making process in product development, ensuring that design choices align with user expectations and improve user experience.

The concept of personas enables teams to step into their users’ shoes, providing a clear perspective on how different users might interact with the product under varied circumstances. For example, consider the diverse motivations behind purchasing a vehicle. A family might prioritise safety and space, opting for a vehicle that offers reliability and room for children and groceries. Conversely, a young professional might value speed, style, and the technology integrated into a luxury sports car, reflecting a different lifestyle and set of needs. By creating detailed personas for each category of buyer, a car manufacturer can tailor designs, features, and marketing strategies to match the specific desires and requirements of each segment, ultimately leading to a product that resonates more profoundly with its intended audience.

In essence, personas act as a bridge between user data and design decisions, ensuring products are crafted with a deep understanding of and empathy for the users they aim to serve. They transform abstract data into relatable, humanised representations of user groups, making it easier for design and development teams to prioritise features, design interfaces, and create experiences that truly meet the users’ needs. This user-centered approach not only enhances usability and satisfaction but also supports the strategic alignment of product development efforts with user expectations, driving more successful outcomes in the competitive landscape.

Creating personas that are diverse and inclusive is not just a practice in empathy but a fundamental approach to designing products that resonate with a broad spectrum of users. Diversity in personas—across age, ethnicity, education, gender, and more—ensures that the product development process reflects the rich tapestry of human experience and needs.

The importance of this diversity cannot be overstated. It brings us closer to understanding the full range of our potential users, allowing us to design solutions that are truly user-centric. It challenges us to look beyond our assumptions and biases, prompting us to question and rethink our design choices. For instance, consider the diversity in the engineering workforce, where females constitute a significant percentage. Representing only male personas in such a context would not only be inaccurate but would also overlook the unique perspectives and needs of female engineers. Similarly, in healthcare fields like nursing and midwifery, where males are in the minority, inclusivity means ensuring their experiences are also considered and addressed.

Stereotypes, such as assuming all women prefer pink, can lead to design decisions that feel superficial or alienating to many users. It’s essential to dig deeper, understanding not just the superficial preferences but the goals, challenges, and contexts of our users’ lives. Decisions should be informed by a comprehensive understanding of the user’s world, including cultural, social, and economic dimensions, ensuring designs are relevant, respectful, and empowering.

Diversity in personas also extends beyond gender to include other dimensions such as ethnicity, age, and educational background. This breadth ensures that the product is accessible and valuable to as wide an audience as possible, fostering inclusivity. For example, designing educational software without considering the diverse learning needs and cultural backgrounds of students would likely result in a tool that benefits only a fraction of the intended users.

In crafting personas, we must strive for a balance that reflects the diversity of our society. This involves recognising and including underrepresented groups, challenging stereotypes, and ensuring that our designs are informed by a genuine understanding of the users we aim to serve. By doing so, we not only create products that are more likely to succeed in the marketplace but also contribute to a more inclusive and equitable digital world.

In conclusion, the development of unbiased, diverse, and inclusive personas is a critical step in the design process. It ensures that products are thoughtfully crafted with the needs, preferences, and contexts of all potential users in mind, leading to solutions that are not only more effective but also more equitable.

Develop prototypes to visualise the system design and functionality:

Conduct usability testing with prototypes to validate design decisions and gather feedback from real or representative users.

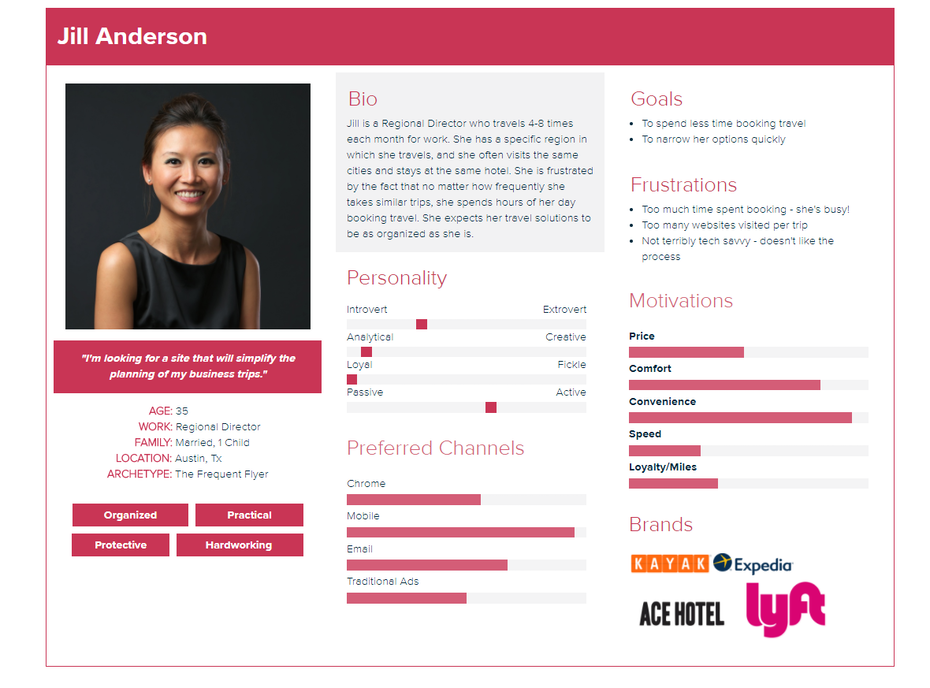

In Agile development, understanding and documenting a product’s purpose, features, functionality, and behaviour is pivotal. This common ground aids both the technical team and the client in collaboratively building the product. Requirements are articulated through initiatives, epics, tasks, and subtasks to ensure clarity and organisation throughout the development process.

For the scope of this subject, your project will be the sole initiative. In broader business contexts, where multiple applications or projects are under development concurrently, each would represent a distinct initiative. This hierarchical structure helps in managing and aligning projects with overarching business goals.

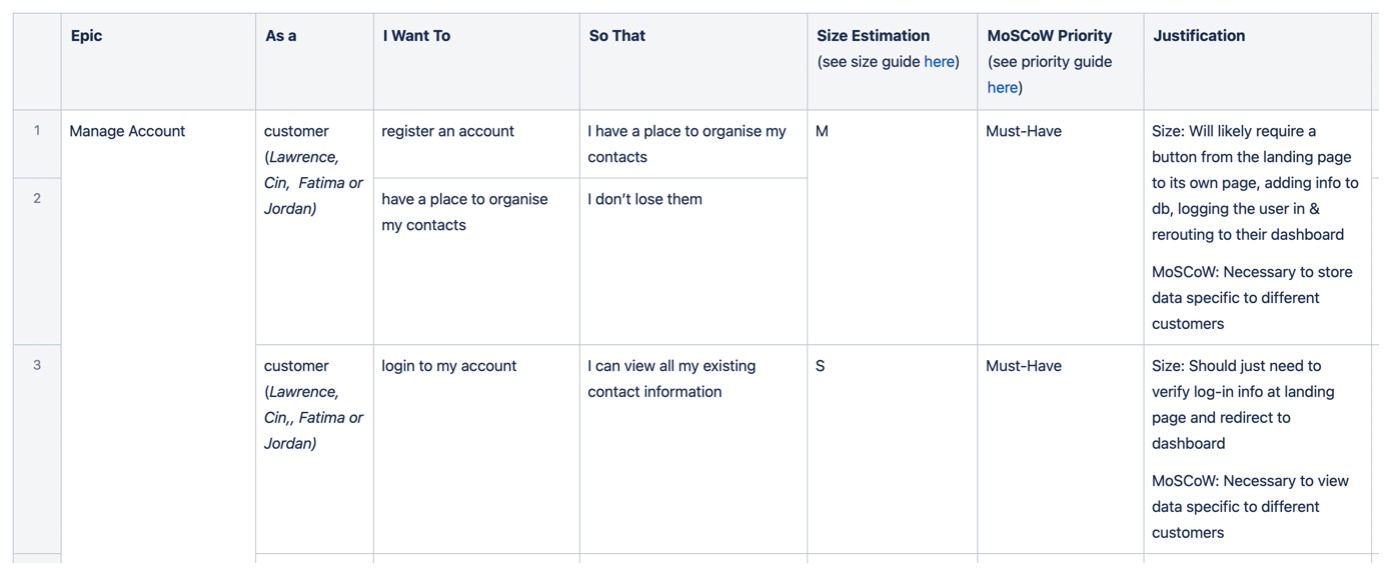

An epic encompasses a large work body, subdividable into smaller, manageable user stories with a shared higher-level objective. Organising work into epics and then into user stories facilitates incremental value delivery. It allows for demonstrating progressive advancements to clients, making the project’s progress tangible and measurable. Epics typically span across more than one sprint and evolve as the project advances, adapting to new insights, client feedback, and team discoveries.

User stories are the fundamental units of work in the Agile framework, representing end goals from the user’s perspective. They are not mere feature lists but expressions of user needs and values. A user story encapsulates what is being built, its purpose, the target user, and the expected value or benefit. Written in non-technical language, it ensures the development work aligns with user expectations and solves real problems.

Initially, user stories are brief, captured in a single sentence that outlines the desired outcome without delving into specifics. The format typically follows:

As a [role], I want to [goal], so that I can [benefit].

For example, a social media platform might frame a user story for uploading profile pictures as:

As an individual user, I want to upload a photo to my profile picture, so that people who search for my name can see a photo of me.

User stories come with estimations, termed as story points, reflecting the effort needed for implementation. Unlike traditional time-based estimates, story points consider work volume, complexity, and uncertainties. Commonly used scales for story points include the Fibonacci sequence and T-shirt sising, aiding in sprint planning and workload management.

During sprint planning, the team employs methods like planning poker to reach a consensus on story points for each user story. This collaborative approach ensures a shared understanding of the workload and aligns team expectations.

The estimation process occurs during sprint planning. There are several ways to estimate the story points of a user story - we will look at planning poker today:

The estimates should be added to your chosen task tracking tool.

A free tool that gamifies the process.

Priority is determined through discussions with the client, focusing on delivering maximum value. The MoSCoW method categorises tasks into must-haves, should-haves, could-haves, and won’t-haves, guiding the team on where to focus their efforts for maximum impact.

Further discussion of the MoSCoW method.

Comprehensive Scrum guide.

Details on running your sprint planning meeting.

Once written, these stories should be documented centrally in the team’s document repository:

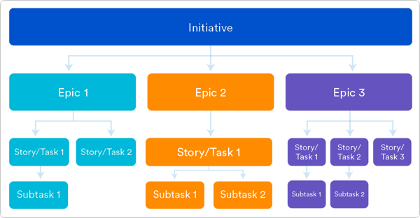

User story mapping fosters team collaboration and offers a holistic view of how backlog stories integrate into the broader product vision. It’s a visual exercise that highlights the project’s scope, deadlines, and goals, ensuring all team members and the client are aligned towards a unified objective.

This is an example of a user story map:

Documenting user stories in a centralised repository ensures that the team and stakeholders have access to up-to-date information about the project’s requirements and progress.

With a solid grasp of user stories, teams are better equipped to embark on the application design phase, ensuring a user-centered development approach that aligns with Agile principles.

Armed with a comprehensive understanding of user stories, it’s time to proceed with designing the application, ensuring a user-centric development process.

It is really important that the user stories, personas and motivational model are consistent with each other, following the 9 principles (CP stands for Consistency Principle):

The natural question to ask is why is it so important that we make sure these artefacts consistent with one another. Firstly, software development teams are increasingly multidisciplinary due to the expansion of application domains where software is essential. The increase in disciplines places greater demands on communication as less knowledge can be assumed. Both technical and non-technical team members are able – and often expected – to contribute to ongoing discussions and decisions about requirements. Given the challenges, we need to create requirements artefacts that are understandable to non-technical users, easily understood by developers, and are consistent with each other in order to improve communication between software developers and industry partners.

Personas and user stories can be used to specify customer requirements. A persona is a description of an archetypal user of a software system, created from research about the potential real users of the software system. A user story statement should relate to both a persona and a goal. A goal is an intended outcome of a persona interacting with a software system. Personas provide the rationale for the existence of user stories. The success of software products is highly dependent on validations performed on users’ goals. The relationships between personas, user stories and goals are critical.

Motivational models present a hierarchical diagram of the goals of a system at a high level of abstraction. They complement personas and user stories which focus more on user needs rather than on system features. The 9 consistency principles help us ensure that personas, user stories and motivational models are consistent with each other, ultimately achieving a better understanding of the requirements among stakeholders.

As teams progress in developing the required artefacts for their projects, it’s crucial to engage in a continuous validation process with the client. This stage often reveals discrepancies between the team’s capabilities and the client’s expectations. In such instances, negotiation becomes essential to align both parties’ visions. Should there be insurmountable differences, consulting a supervisor for guidance is advisable.

The cornerstone of validation is running usability tests with the client, leveraging the developed prototypes. These tests are designed around specific tasks that embody the core functionalities captured in the user stories. For instance, consider a user story focused on a user logging in and reviewing their purchase history. A high-fidelity prototype should enable a simulation of this scenario, establishing a clear success narrative. Any deviation from this outcome indicates a need for further refinement.

To organise this testing phase effectively, the team should schedule a session with the client, appointing a test facilitator to guide the process. This individual is responsible for directing the client through the predetermined tasks, observing their interactions, and gathering qualitative feedback. Concurrently, a designated minute taker should document all observations and suggestions, no matter how minor they may seem. This meticulous collection of feedback is invaluable, potentially saving considerable time and effort by preempting the need for significant alterations during later development stages.

Tools like Maze can streamline this process, offering an automated platform to test high-fidelity prototypes and gather user insights efficiently.

Upon completing these steps and achieving consensus with the client, the team can finalise the project specifications. This comprehensive documentation includes the motivational model, personas, prototypes, and user stories, each reflecting the collaborative effort and mutual agreement between the team and the client. This cohesive set of specifications ensures that the project is well-positioned to move forward into the development phase, grounded in a clear understanding of the user needs and project goals.

Combine all gathered information into a comprehensive specification document, including: